History of the town of Puy-en-Velay |

At the end of the 6th century, during the time of Gregory of Tours, the first historian to mention it, the city of Puy, or better yet Anis (Anicium), did not yet exist. This designation referred to a mountain that then dominated the town of Anis, now called Le Puy, a word derived from the Aquitanian puich or puech, meaning height or eminence. From its origin, we see the city of Puy or Anis, located in Velay, emerge under the dependency of its bishops, among whom we count eleven saints. The precise date of the foundation of this episcopal seat is quite uncertain, and we hardly know the names of the bishops of Velay who occupied it prior to the 6th century.

At the end of the 6th century, during the time of Gregory of Tours, the first historian to mention it, the city of Puy, or better yet Anis (Anicium), did not yet exist. This designation referred to a mountain that then dominated the town of Anis, now called Le Puy, a word derived from the Aquitanian puich or puech, meaning height or eminence. From its origin, we see the city of Puy or Anis, located in Velay, emerge under the dependency of its bishops, among whom we count eleven saints. The precise date of the foundation of this episcopal seat is quite uncertain, and we hardly know the names of the bishops of Velay who occupied it prior to the 6th century.

The two historians of this church, Gissey and Theodore, report, in truth, several circumstances of their lives; but they rely only on breviaries or legends of too modern an authority, and thus very questionable. They give this church its first bishop, Saint George, whom they make a disciple of Saint Peter, and whose collegiate church in the city of Puy preserves his relics. After him, Saint Marcellin and Saint Paulier are mentioned, and it is said that his successor, Saint Evode, commonly called Voisy, transferred the episcopal seat, either in the 3rd or the 6th century (there is much disagreement on this point), located then at Ruessium or Vallava, civitas Vellavorum, from Saint Paulier to the city of Anicium. According to another version, this transfer only occurred between the years 877 and 919, by the efforts of Bishop Norbert, who, on this occasion, transferred from Vallava to Puy the relics of Saint George and Saint Marcellin.

The two historians of this church, Gissey and Theodore, report, in truth, several circumstances of their lives; but they rely only on breviaries or legends of too modern an authority, and thus very questionable. They give this church its first bishop, Saint George, whom they make a disciple of Saint Peter, and whose collegiate church in the city of Puy preserves his relics. After him, Saint Marcellin and Saint Paulier are mentioned, and it is said that his successor, Saint Evode, commonly called Voisy, transferred the episcopal seat, either in the 3rd or the 6th century (there is much disagreement on this point), located then at Ruessium or Vallava, civitas Vellavorum, from Saint Paulier to the city of Anicium. According to another version, this transfer only occurred between the years 877 and 919, by the efforts of Bishop Norbert, who, on this occasion, transferred from Vallava to Puy the relics of Saint George and Saint Marcellin.

In any case, the beginnings of the city of Puy must have been difficult, as it does not seem that it established itself in a time frame shorter than that which extends from the end of the 10th century to the early years of the 12th. Anicium was still just a village, whose domain belonged to the Dukes of Aquitaine, particular counts of Velay, when King Raoul granted, on April 8, 924, with the consent of one of them, William II or III, his vassal, to the Bishop of Velay, Adalard, the village adjoining the church of Notre-Dame-du-Puy, with all its dependencies, namely; the rights of tolls or customs (teloneum), of market, of jurisdiction, and of mint.

The Bishop of Puy thus enjoyed, from then on, royal rights; however, it cannot be affirmed that Adalard was the first to mint coins; an undeniable fact is that his successors had coins struck that were called podienses. The charter of Raoul was confirmed in 955 by King Lothaire, in favor of Bishop Gotescale, who had approached him in Laon; and, in 1134, by Louis the Fat, whose diploma, dated in Orléans, first confuses Anis (Anicium) with Le Puy and qualifies it as a city. In this charter, Louis the Fat also granted the castle of Corneille to Bishop Humbert; but he did not mention, any more than had Kings Lothaire and Raoul, the county of Velay, which proves that the Bishops of Puy did not soon unite it with their domain. If we are to believe some authors, they were only subject to the Holy See since 998, by privilege granted to Bishop Théotard; it was only later, in 1051, that Pope Leo IX had added to this privilege the right to wear the pallium.

The church of Notre-Dame-du-Puy already had a great reputation for holiness, and the faithful flocked to it from all directions. The very pious King Robert visited it on his return from Brioude (1229). Bishop Aymar de Monte forced the Viscount of Polignac to renounce his claims on it (1087); so that the power of the prelates gradually increased through an infinity of endowments, emanating from the superstitious devotion of the time, and from concessions of several strongholds in Velay (1169). Louis the Young was the first king of France, of the third race, to levy a subsidy in the city of Puy, where he came twice (1138-1146).

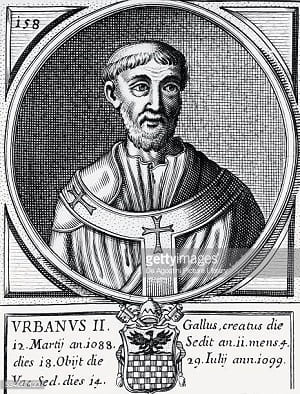

This city had received within its walls the popes Urban II (1095), Gelasius II and Callistus II, his successor (1118), Alexander II (1162), and Alexander III (1165). A council was held there (1130), in which Innocent II was unanimously recognized as pope, and Anacletus, his competitor, was excommunicated; and when the heresy of the Albigenses became alarming, a legate from Pope Alexander III convened another council there (1381) to combat it. It would be too lengthy to enumerate all the kings, princes, or lords, all the queens and great ladies, all the pilgrims and others of every condition, sex, and age whom the reputation of the Virgin Mary of Puy brought in crowds; we will suffice to say that there was, in 1406, on the day of the Annunciation, due to the simultaneity of this feast with Good Friday and the special indulgence attached to it, such a gathering of pilgrims at Notre-Dame du Puy that no less than two hundred people were suffocated in this prodigious influx.

This city had received within its walls the popes Urban II (1095), Gelasius II and Callistus II, his successor (1118), Alexander II (1162), and Alexander III (1165). A council was held there (1130), in which Innocent II was unanimously recognized as pope, and Anacletus, his competitor, was excommunicated; and when the heresy of the Albigenses became alarming, a legate from Pope Alexander III convened another council there (1381) to combat it. It would be too lengthy to enumerate all the kings, princes, or lords, all the queens and great ladies, all the pilgrims and others of every condition, sex, and age whom the reputation of the Virgin Mary of Puy brought in crowds; we will suffice to say that there was, in 1406, on the day of the Annunciation, due to the simultaneity of this feast with Good Friday and the special indulgence attached to it, such a gathering of pilgrims at Notre-Dame du Puy that no less than two hundred people were suffocated in this prodigious influx.

Before embarking on the journey to the Holy Land, King Philip Augustus advanced to Puy to invoke the Virgin's help and make her favorable to his undertaking (1188). A few years later, disputes arose between the Bishop of Puy, Robert of Mehun, and the inhabitants of this city, in which the king intervened in favor of the bishop, who was soon murdered at Saint-Germain by a certain Bertrand de Cares, whom he had excommunicated.

Before embarking on the journey to the Holy Land, King Philip Augustus advanced to Puy to invoke the Virgin's help and make her favorable to his undertaking (1188). A few years later, disputes arose between the Bishop of Puy, Robert of Mehun, and the inhabitants of this city, in which the king intervened in favor of the bishop, who was soon murdered at Saint-Germain by a certain Bertrand de Cares, whom he had excommunicated.

Later, the inhabitants sought once again to free themselves from the temporal power of their prelate; but he, supported by royal authority, always managed to bring them to reason (1219-1236). Saint Louis had an interview in Puy with James, King of Aragon, and stayed there for three days on his return from Palestine; he received the right of lodging from the bourgeois, the bishop, and the chapter (1243-1254). However, a deplorable sedition troubled Puy regarding some soldiers who had pillaged the surrounding countryside. Two judicial officers perished as victims of popular exasperation, and on this occasion, the commune remained deprived for a long time of its consulate and its privileges (1277). Philip the Bold and Philip the Fair also stopped in Puy, one in 1283 and the other in 1285. The bishop, Jean de Cuménis, was among the prelates who supported this last prince against Pope Boniface VIII and appealed to the next council of the Holy See (1283-1285-1313).

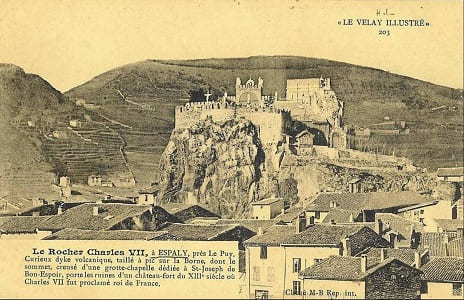

During the captivity of King John, the inhabitants of Puy took up arms and stopped the English raids near Clermont (1359). Charles VI, hoping to obtain some alleviation of his bouts of madness, undertook two pilgrimages to Puy, where he touched the écrouelles (a type of disease). The same king fixed the number of consuls in the city at six, and not finding the color of their robes, capes, and hoods to be in good taste, he ordered that from then on, instead of being made of blue cloth, they should be made of scarlet (1389-1394). At the beginning of the following century, the lords of Velay had to struggle against both the English and the Duke of Burgundy. They locked themselves in the city of Puy, which the duke had tried to surprise, hoping that its submission would lead to that of Vivarais and Gévaudan. Their resistance discouraged the attackers, commanded by the Prince of Orange (1419). Shortly after, the Dauphin, later Charles VII, made his entry into Puy after having subdued Languedoc, and created knights out of all those who had distinguished themselves against the Burgundians; he was at the Château d'Espaly, near Puy, when he learned of his father's death, and it was there that he was hailed as king of France (1420-1422).

During the war of the Good Public, Velay, despite the efforts of the Count of Polignac and the Bishop of Puy, remained loyal to the king; the clever measures of the governor of the province prevented the city from declaring itself (1460). The Queen of France, Charlotte of Savoy, visited Puy in 1470, and Louis XI himself came there six years later on a pilgrimage to make a novena. In 1482, Puy was afflicted by a pestilent fever, preceded by a horrible storm that destroyed the harvest and caused famine. The plague claimed seventeen thousand lives, who were hastily buried at Clusel, in the Martouret square, at the very spot where the town hall now stands. The plague broke out again in Puy in 1521 and wreaked havoc again in 1547. The terrified inhabitants sought refuge in the countryside; the consuls themselves left the city, where grass soon began to grow in the streets. In a period of security, devotion had attracted three illustrious visitors to Puy: Charles VIII and Francis I, kings of France (1495-1516), and John Stuart, regent of Scotland (1533). Henry II, in 1548, summoned the holding of the Great Days in this city, with a commission to extirpate the unfortunate Lutheran sect. Some heretics were condemned to fire there.

During the war of the Good Public, Velay, despite the efforts of the Count of Polignac and the Bishop of Puy, remained loyal to the king; the clever measures of the governor of the province prevented the city from declaring itself (1460). The Queen of France, Charlotte of Savoy, visited Puy in 1470, and Louis XI himself came there six years later on a pilgrimage to make a novena. In 1482, Puy was afflicted by a pestilent fever, preceded by a horrible storm that destroyed the harvest and caused famine. The plague claimed seventeen thousand lives, who were hastily buried at Clusel, in the Martouret square, at the very spot where the town hall now stands. The plague broke out again in Puy in 1521 and wreaked havoc again in 1547. The terrified inhabitants sought refuge in the countryside; the consuls themselves left the city, where grass soon began to grow in the streets. In a period of security, devotion had attracted three illustrious visitors to Puy: Charles VIII and Francis I, kings of France (1495-1516), and John Stuart, regent of Scotland (1533). Henry II, in 1548, summoned the holding of the Great Days in this city, with a commission to extirpate the unfortunate Lutheran sect. Some heretics were condemned to fire there.

The majority of the population of Puy was Catholic when the wars of religion broke out. The Baron des Adrets, unable to go there personally to subdue the city, dispatched Blacons, his lieutenant, whom he put at the head of seven to eight thousand men (1562). He arrived at dawn before the square, defended by the elite of the nobility of Velay. Vigorously repulsed, he pillaged the small village of Aiguilhe, the Cordeliers, the Jacobins, and went to take Espaly, the castle of the Bishop of Puy, Sénéctère; he destroyed its fortifications and walls, then returned against the city, but all his attacks failed, and he was forced to lift the siege with losses. To guard against new attacks from the Protestants, who, fortunately, did not renew them.

The majority of the population of Puy was Catholic when the wars of religion broke out. The Baron des Adrets, unable to go there personally to subdue the city, dispatched Blacons, his lieutenant, whom he put at the head of seven to eight thousand men (1562). He arrived at dawn before the square, defended by the elite of the nobility of Velay. Vigorously repulsed, he pillaged the small village of Aiguilhe, the Cordeliers, the Jacobins, and went to take Espaly, the castle of the Bishop of Puy, Sénéctère; he destroyed its fortifications and walls, then returned against the city, but all his attacks failed, and he was forced to lift the siege with losses. To guard against new attacks from the Protestants, who, fortunately, did not renew them.

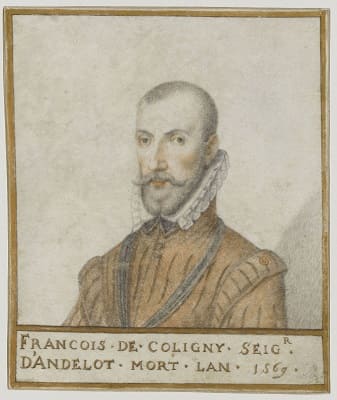

Antoine de la Tour de Saint-Vidal, governor of Velay and Upper Vivarais, fortified Le Puy and summoned the nobility. Later, new fortifications were added to Puy. The Protestants conspired to surrender the place; but the seneschal of Rochebonne discovered and thwarted the conspiracy (1568). At the time of the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre, Bishop Sénéctère refused to carry out the bloody orders of the court. He gathered the Protestants in his palace, shared the king's letters with them, and touched them so much with his magnanimity that they converted on the spot (1572). The city soon joined the League, and François de Coligny vainly tried to surprise it (1585). La Tour de Saint-Vidal, a strong supporter of the Guise, then made the inhabitants swear the Holy Union against Henry III. A delegation from the city of Toulouse completed their persuasion: the bishop set the example. The king, dissatisfied, appointed François de Chaste as governor of Velay; but the inhabitants of Puy persisted in recognizing this title only for Baron de Saint-Vidal. In his absence, they chose twenty-four of their own, to whom they entrusted the main authority, imitating the council of the Sixteen of Paris and that of the Eighteen of Toulouse. Upon the death of Henry III, Chaste and the bishop recognized Henry IV, while the inhabitants of Puy, led by Saint-Vidal, made preparations for defense.

The League members of this city published an arrest from the parliament of Toulouse, pronouncing the confiscation of the property of the politicians, to allocate the proceeds to war expenses. They then went on a campaign, assaulted the castle of Polignac, razed its fortifications, and attempted a raid on the castles of Ceyssac and Espaly (1589-1590). More fortunate, Saint-Vidal returned, with the title of governor of Gévaudan, at the head of five to six thousand men; he occupied, by capitulation, Espaly, whose fortifications he blew up. But in a reconciliation meeting, after getting into a quarrel with Chaste, he fought a duel with him and was killed. The League members of Puy gave him a magnificent funeral and renewed their oath not to recognize Henry of Bourbon or anyone from his party: the effigy of the Béarnais was even publicly burned. The royalists then attempted to surprise Puy during the night; but their plan was revealed, and they suffered many losses.

The League members of this city published an arrest from the parliament of Toulouse, pronouncing the confiscation of the property of the politicians, to allocate the proceeds to war expenses. They then went on a campaign, assaulted the castle of Polignac, razed its fortifications, and attempted a raid on the castles of Ceyssac and Espaly (1589-1590). More fortunate, Saint-Vidal returned, with the title of governor of Gévaudan, at the head of five to six thousand men; he occupied, by capitulation, Espaly, whose fortifications he blew up. But in a reconciliation meeting, after getting into a quarrel with Chaste, he fought a duel with him and was killed. The League members of Puy gave him a magnificent funeral and renewed their oath not to recognize Henry of Bourbon or anyone from his party: the effigy of the Béarnais was even publicly burned. The royalists then attempted to surprise Puy during the night; but their plan was revealed, and they suffered many losses.

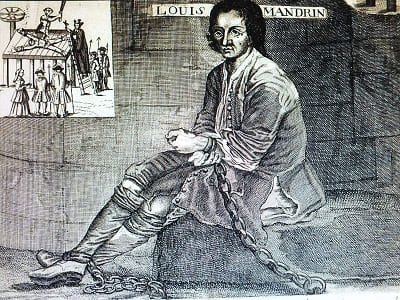

Their main leaders, among them Seneschal Chaste, perished in this tumult. Several inhabitants suspected of collusion were imprisoned, and the most notable were hanged in the Martouret square. Finally, abandoned by all their allies, forced to keep watch every other night, to dig during the day, to pay contributions in advance, and fearing the incursion of the Croquants, the inhabitants of Puy renounced warring and signed peace with Henry IV, who granted them tax exemption for five years (1591-1596). Since that time, the history of Puy has presented only a few secondary events. The only one that seems worth mentioning is the daring venture of the famous thief Mandrin, who, having entered Puy despite the vigilance of the officials, plundered the house of the captain general of the farms, broke into the prisons from which he freed several detainees, and quietly withdrew to commit his robberies elsewhere (1754).

Le Puy, capital of the ancient Velay and seat of the specific estates of this region, was once a very strong military position and was considered the sixth city of Languedoc. Its coat of arms, which it was authorized to adopt under the Restoration by a royal ordinance, is semé of France with a silver eagle in a lowered flight superimposed on the whole; the shield is adorned with two green palmes linked by azure. These arms were granted to it under the Capetian dynasty around the year 992, at the request of Guy Foulques, Bishop of Velay. Today, Le Puy has an agricultural society, sciences and arts, a museum of paintings, statues, and antiquities, a library, a college, a first instance court, and a commercial court. This city is still the seat of a diocese: it has more than 15,000 souls; the department of Haute-Loire, of which it is the capital, contains nearly 299,000 inhabitants, and the district has 132,500. Espaly, in the same canton as Puy, has about 1,200.

Le Puy, capital of the ancient Velay and seat of the specific estates of this region, was once a very strong military position and was considered the sixth city of Languedoc. Its coat of arms, which it was authorized to adopt under the Restoration by a royal ordinance, is semé of France with a silver eagle in a lowered flight superimposed on the whole; the shield is adorned with two green palmes linked by azure. These arms were granted to it under the Capetian dynasty around the year 992, at the request of Guy Foulques, Bishop of Velay. Today, Le Puy has an agricultural society, sciences and arts, a museum of paintings, statues, and antiquities, a library, a college, a first instance court, and a commercial court. This city is still the seat of a diocese: it has more than 15,000 souls; the department of Haute-Loire, of which it is the capital, contains nearly 299,000 inhabitants, and the district has 132,500. Espaly, in the same canton as Puy, has about 1,200.

In addition to the famous figures we have had the occasion to mention throughout this notice, Puy saw the birth of Pope Clement IV, elected in the 13th century; the literateur Irail; the painter Boyer; the Guy family, father and son, both painters, one nicknamed the Great, the other the Illustrious, the first known in Italy as Guide Franciste, the second in Paris, where he gained a reputation partly justified by one of his paintings preserved in the church of Notre-Dame-du-Puy. We will also mention the Baron de Latour-Maubourg, Marshal of France; and Cardinal Melchior de Polignac, a member of the French Academy, whose name belongs to our political and literary history; indeed, the negotiator of the Peace of Utrecht, the author of Anti-Lucretius occupies an important place among the great men of the time of Louis XIV.

In addition to the famous figures we have had the occasion to mention throughout this notice, Puy saw the birth of Pope Clement IV, elected in the 13th century; the literateur Irail; the painter Boyer; the Guy family, father and son, both painters, one nicknamed the Great, the other the Illustrious, the first known in Italy as Guide Franciste, the second in Paris, where he gained a reputation partly justified by one of his paintings preserved in the church of Notre-Dame-du-Puy. We will also mention the Baron de Latour-Maubourg, Marshal of France; and Cardinal Melchior de Polignac, a member of the French Academy, whose name belongs to our political and literary history; indeed, the negotiator of the Peace of Utrecht, the author of Anti-Lucretius occupies an important place among the great men of the time of Louis XIV.

The commerce of Puy primarily consists of lace, seeds, and vegetables that this city ships to southern departments; prepared and sewn leathers in bags, convenient for transporting wine, used to be one of its industrial branches, which has greatly diminished. Despite its commercial decline, Puy still has factories producing white and black lace, wine bags or sacks, blankets, and common woolen fabrics, a spinning mill, a wool dyeing facility, a nail factory, foundries for pots, cauldrons, bells, as well as objects that muleteers from central and southern France have been sourcing for more than a century; tanneries for goat skins, a paper mill, and lime kilns.

The city, which develops like an amphitheater on the slope of Mont-Corneille near the small rivers of Borne and Doïaison, a league from the Loire where they flow, presents a very picturesque aspect. While it is beautiful in perspective, it does not gain by being examined internally; its poorly punctured, narrow, unclean streets, with a slope inaccessible to vehicles in some parts of the high city, paved with debris from the volcanic rock of Corneille, rendered more or less slippery by rain, ice, or drought, pose dangers to the stranger who is not used to traversing them.

However, in this city, one can distinguish the promenade of Breuil. As for its monuments, there are the cathedral of Notre-Dame, noted for its boldness, bizarre construction, and magnificent façade; the church of Saint-Laurent, which the memory of Du Guesclin, whose remains are interred there, recommends to the veneration of all Frenchmen; that of Saint-Michel, which would have nothing particular except its Gothic antiquity, if it did not acquire real value due to the pyramidal rock crowned by its needle bell tower, a true obelisk blending in the distance with the peculiarity of the cone represented by the rock; finally, a round building called the Temple of Diana, and among modern constructions, the prefecture building, the town hall, the Hôtel-Dieu, the general hospital, the seminary, and the cavalry barracks located in the Saint-Laurent suburb, near the Estrouilhas bridge. History of the Cities of France published by Aristide Guilbert

Former holiday hotel with a garden along the Allier, L'Etoile Guest House is located in La Bastide-Puylaurent between Lozere, Ardeche, and the Cevennes in the mountains of Southern France. At the crossroads of GR®7, GR®70 Stevenson Path, GR®72, GR®700 Regordane Way, GR®470 Allier River springs and gorges, GRP® Cevenol, Ardechoise Mountains, Margeride. Numerous loop trails for hiking and one-day biking excursions. Ideal for a relaxing and hiking getaway.

Copyright©etoile.fr