Tourism in Pont-de-Montvert at the time |

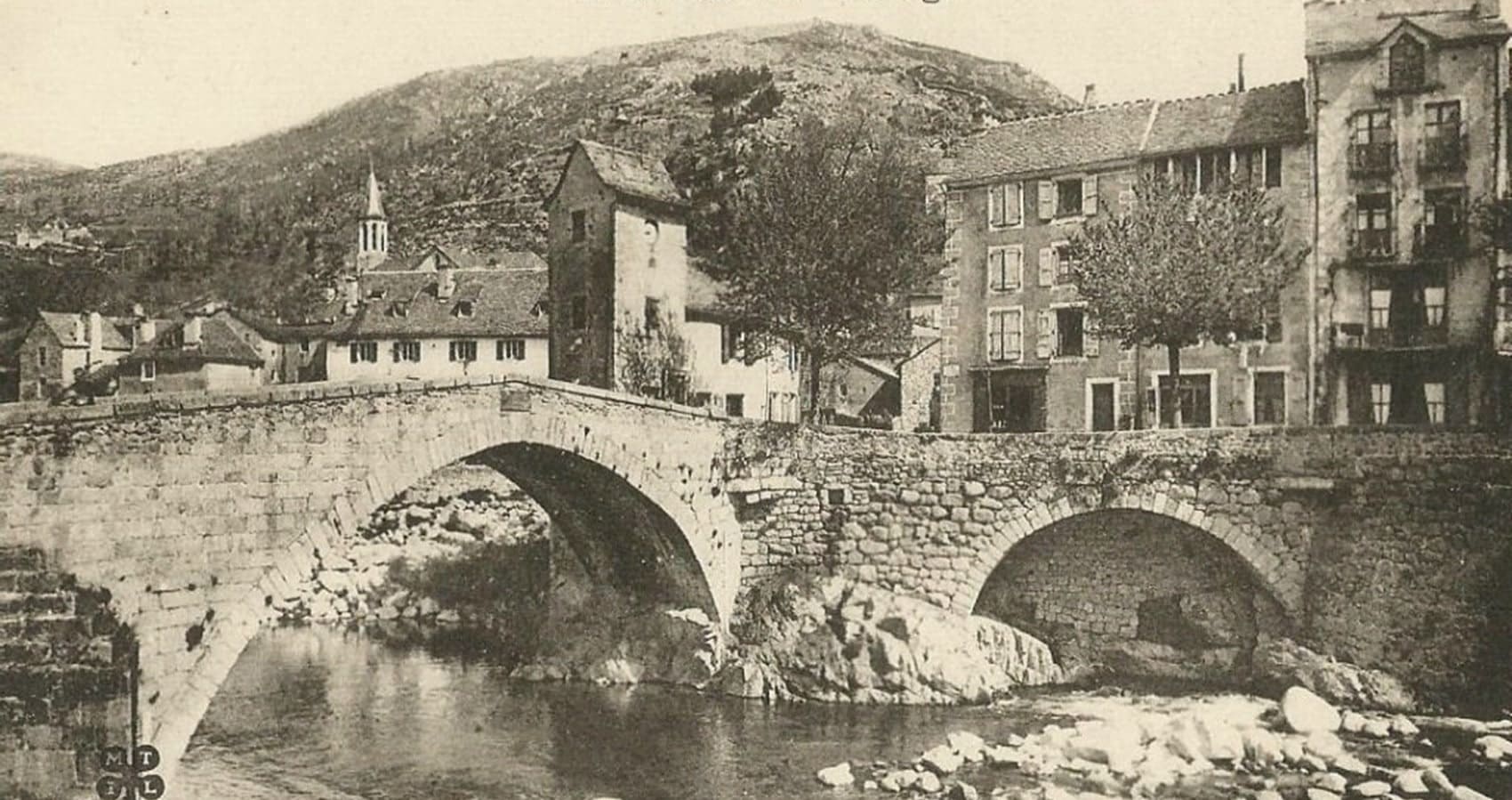

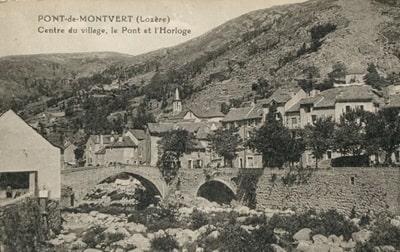

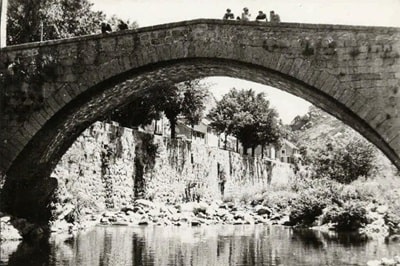

At the end of the 19th century, the tourist appeal of Pont-de-Montvert was primarily linked to its status as the gateway to Mont Lozère and the wild beauty of its Cévennes landscape. The arrival of Robert Louis Stevenson in 1878, with his donkey Modestine, marked the village, although the impact of his travel narrative would only be felt later. Visitors during this period were mainly travelers seeking authenticity and rest, away from the hustle and bustle of big cities. Many were already hikers, sensitive to nature and interested in the tragic history of the religious wars. The village then offered the essentials: a simple inn for lodging and dining, as well as direct contact with the local Protestant culture and the stories of the Camisards. The famous medieval bridge and the Tarn River were already the main visual points of interest for these early tourists.

Pont-de-Montvert (882 m.; buses to Florac, Génolhac, Mende; Hotel de la Truite Enchantée, 12 rooms, tel. 3), 607 inhabitants, on both banks of the Tarn, at the exit of the valleys of Martinet (left bank) and Rieumalet (right bank), with a reforestation perimeter of 1,284 hectares, was one of the most ardent centers of Protestantism in the Cévennes. It was here that the uprising of the Camisards began on July 24, 1702, with the murder of the archpriest of Chayla.

Pont-de-Montvert (882 m.; buses to Florac, Génolhac, Mende; Hotel de la Truite Enchantée, 12 rooms, tel. 3), 607 inhabitants, on both banks of the Tarn, at the exit of the valleys of Martinet (left bank) and Rieumalet (right bank), with a reforestation perimeter of 1,284 hectares, was one of the most ardent centers of Protestantism in the Cévennes. It was here that the uprising of the Camisards began on July 24, 1702, with the murder of the archpriest of Chayla.

The village is dominated to the north by Mount Lozère. 5 km to the southwest, Grizac, a hamlet with an old castle, now a farm, where Pope Urban V (1309-1370) was born. From Pont-de-Montvert to Bleymard, 23 km to the north via (6 km 5) Finiels, where you join the road to Mount Lozère; at the Col de Montmirat via Runes.

From Pont-de-Montvert to Florac, the Tarn valley is still carved into ancient rocks. Viala, a hamlet where the road to the Col de Montmirat branches off to the right.

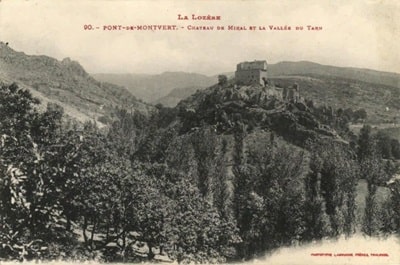

The N. 598 road, very beautiful, descends the Tarn valley at a great height above the sheer rocks of the right bank. You pass in front of the Château de Miral, perched on a promontory, on the left. Cocurès: beautiful view of the cliffs of the Méjean causse.

The valley widens; you descend to cross the Tarn and leave Bédouès, which has a 14th-century church founded by Pope Urban V, on the left.

On the right, Château d'Arigès. You reach, at the confluence of the Tarn and the Tarnon (535 m.), the N. 107 road, which you follow to the left while going up the Tarnon valley, and you cross this river before (48 km 5) Florac.

At the exit of Génolhac, the N. 106 road crosses the Homol and leaves the road to Florac on the right. Belle-Poêle, a hamlet beyond which you descend windingly to the left bank of the Luech, which you cross when entering Chamborigaud.

From Pont-de-Montvert to Florac, the Tarn valley is still carved into ancient rocks. Viala, a hamlet where the road to the Col de Montmirat branches off to the right.

The N. 598 road, very beautiful, descends the Tarn valley at a great height above the sheer rocks of the right bank. You pass in front of the Château de Miral, perched on a promontory, on the left. Cocurès: beautiful view of the cliffs of the Méjean causse.

The valley widens; you descend to cross the Tarn and leave Bédouès, which has a 14th-century church founded by Pope Urban V, on the left.

On the right, Château d'Arigès. You reach, at the confluence of the Tarn and the Tarnon (535 m.), the N. 107 road, which you follow to the left while going up the Tarnon valley, and you cross this river before (48 km 5) Florac.

At the exit of Génolhac, the N. 106 road crosses the Homol and leaves the road to Florac on the right. Belle-Poêle, a hamlet beyond which you descend windingly to the left bank of the Luech, which you cross when entering Chamborigaud.

Chamborigaud (300 m.; railway); coal mines. 1 km to the east, beautiful curved viaduct of the Nîmes line, 60 m high, over the Luech. You leave the road to Bessèges, which descends the wild gorge of the Luech, on the left. The N. 106 road climbs in loops over the ridge separating the Cèze basin from that of the Gardon. La Tavernole, which is connected by a winding and picturesque road of 10 km to Sainte-Cécile-d'Andorge.

Portes (578 m.), with a beautiful castle from the 14th and 17th centuries, perched at the highest point of the road, which now descends in large curves. Intersection where the road to La Grand-Combe (6 km) branches off to the right via the Col de Malpertus (390 m.). Le Pradel (391 m.). The road, always uneven, slips between the hills, descends through the scrubland overlooking the Gardon valley on the right, and finally opens into the Alès plain. To the right, forges and blast furnaces of Tamaris.

***

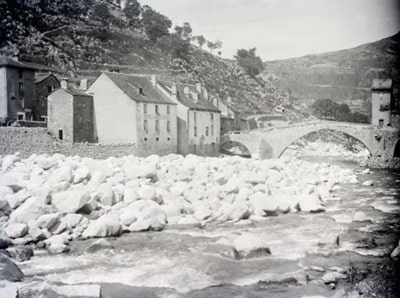

Before Pont-de-Montvert, the rocky walls overlooking the road along the Tarn glisten with the large ice cascades formed by the runoff and the polar cold of recent days. Traditionally: a brief stop in the village.

Before Pont-de-Montvert, the rocky walls overlooking the road along the Tarn glisten with the large ice cascades formed by the runoff and the polar cold of recent days. Traditionally: a brief stop in the village.

It was my brother who introduced me to Pont-de-Montvert over forty years ago... How did he discover this corner of Lozère himself? I can’t remember too well; he wandered a lot, he loved to drive. We fished together in the area for years, then Tanh got married, he moved to the southwest, near those Pyrenees to which he became profoundly attached and near which death took him. He must have been five or six years old when he entered our family, leaving behind his native Vietnam and his worst memories.

Tanh grew up with us, haphazardly. He often saw me preparing for my outings, and his eyes lit up when I unpacked all that little equipment: pliers, hooks, spools of line, feathers, floats. One day, he insisted on accompanying me to the water's edge... The meticulous care, ingenuity, and patience were part of his native qualities: he would have been an extraordinary fisherman. But there was also in this guy an inexhaustible spirit of competition: our complicity was never quite what I would have liked it to be. Yet, his love for fishing and nature was deep, and I remember with emotion our exchanges by the Tarn.

Since that Pentecost weekend in 1973 when I arrived at Pont-de-Montvert, I have often reflected on my absurd attachment to this piece of meteorite that is the south of Lozère. Could I have lived there? I don't know; further up, yes, towards Mende and the Lot valley, the Aubrac and the Margeride, most certainly. But the Cévennes have something terrible in their geography, Jean Carrière describes all this admirably in *L'entier de Maheux*. And yet I love this land: the Cévennes are primarily the Cévenols, I understand myself. (The power of a landscape, its influence on the soul of a population does not always follow logical slopes: the aerial splendor of the Provençal Alps, for example, contrasts with the harshness of their villages, while the roughness and, let’s say it, the ugliness of certain landscapes of the Cévennes have not reached the kindness of their populations.)

I remember that evening towards the end of the eighties, there, in a rural gîte by the Rieumalet. Pink flames danced on the embers, lighting up our profiles. We were smiling at each other. At one point, the evening was also dedicated to the memory of Paul, whom some of us knew well. I had met him one June evening, two or three years earlier. We were both coming back from fishing. At first glance, nothing was more austere and perfectly congenial than this five-foot-eleven Parisian who was quiet, thin as a sparrow, with a very low voice.

I remember that evening towards the end of the eighties, there, in a rural gîte by the Rieumalet. Pink flames danced on the embers, lighting up our profiles. We were smiling at each other. At one point, the evening was also dedicated to the memory of Paul, whom some of us knew well. I had met him one June evening, two or three years earlier. We were both coming back from fishing. At first glance, nothing was more austere and perfectly congenial than this five-foot-eleven Parisian who was quiet, thin as a sparrow, with a very low voice.

At the Café du Commerce, we had drunk beer while shelling pistachios. I was struck by the words Paul chose to describe, to emphasize the revelation that the wildness of those Celtic moors, the violence of their torrents, and the gentleness of their streams had been for him. This was five or six years earlier. He had come from Paris where he practiced, we don’t quite know what professional occupation. A passionate fly fisherman, he wanted to discover the Tarn and the Lot, which he spoke of as among the most beautiful trout rivers in Europe.

I later learned that it was also for him a way to heal from the memory of a woman. So, he arrived one April morning, and to everyone’s astonishment, he stayed there; he didn’t return to Paris. Everything a conventional novel might imagine happened, even a few nights under the stars. He lived in a gîte with a bit of money, the clothes he had brought in an old suitcase, and his battered Peugeot...

I later learned that it was also for him a way to heal from the memory of a woman. So, he arrived one April morning, and to everyone’s astonishment, he stayed there; he didn’t return to Paris. Everything a conventional novel might imagine happened, even a few nights under the stars. He lived in a gîte with a bit of money, the clothes he had brought in an old suitcase, and his battered Peugeot...

But he had found his place. He did odd jobs, repaired fence walls, took care of animals, maintained cars, and even gave a few fly-fishing lessons; finally, he successfully passed a modest exam to become a worker for the departmental road service and rented a small house in the village. This social turnaround naturally ensured him real fame in the region. But it was also his fishing talents that made him known. I know what I’m talking about. In Time and Places: Autumn Mist by Patrick Heurley

***

I would like to have a guide who could take me to Pont-de-Montvert, and leave at once, said Toinon. Go to Pont-de-Montvert, madam! But don’t you know that the heretics of the west... I know everything that’s said, but it doesn’t matter; I want to leave right now for Pont-de-Montvert and find a guide. Do you know one? Thomas Rayne turned his cap in every direction, scratched his ear, and finally said: We are so afraid of the fanatics, madam, since they have gathered armed, that for neither gold nor silver will you find anyone willing to step out of the city. But the postilion who brought me... can’t he take me to Pont-de-Montvert? The postilion! Leave here! And here comes the night! Ah! madam, it’s clear you are a stranger. Even if you covered their saddles with gold coins, they wouldn’t move, the postilions!

I would like to have a guide who could take me to Pont-de-Montvert, and leave at once, said Toinon. Go to Pont-de-Montvert, madam! But don’t you know that the heretics of the west... I know everything that’s said, but it doesn’t matter; I want to leave right now for Pont-de-Montvert and find a guide. Do you know one? Thomas Rayne turned his cap in every direction, scratched his ear, and finally said: We are so afraid of the fanatics, madam, since they have gathered armed, that for neither gold nor silver will you find anyone willing to step out of the city. But the postilion who brought me... can’t he take me to Pont-de-Montvert? The postilion! Leave here! And here comes the night! Ah! madam, it’s clear you are a stranger. Even if you covered their saddles with gold coins, they wouldn’t move, the postilions!

And the heretics! Don’t you know that the sight of a carriage attracts them like honey attracts flies! What cowardice! Toinon exclaimed angrily, stamping her foot; to not find a man of heart and resolution! If madam would wait until the day after tomorrow, a convoy of muleteers from Nîmes is due to arrive, heading to the Rouergue; they should pass very close to Pont-de-Montvert. If they dare, despite the rumors, to venture into the west, then you can follow them. But one hour, one minute late, is of fatal consequence for me! I will give, I tell you, twenty, thirty louis, if necessary... but find me a guide, for heaven's sake, a guide!

After thinking for a while, the innkeeper slapped his forehead and exclaimed: Perhaps the poor young black woman, who also says she is in a hurry to get to the west, will agree to accompany you, madam. Who is this woman? A poor girl dressed in mourning, who travels on foot. She arrived about an hour ago; she is resting now, but she wants to set off again at sunset, despite what anyone may have told her. By Saint Thomas, my patron! she seems to fear neither God, nor devil, nor fanatic, nor prophet... What a girl! Jesus-God! a steel corslet would suit her better than a bodice! And where is she going? To Saint-Andéol-de-Clerguemot; it’s two leagues from Pont-de-Montvert.

After thinking for a while, the innkeeper slapped his forehead and exclaimed: Perhaps the poor young black woman, who also says she is in a hurry to get to the west, will agree to accompany you, madam. Who is this woman? A poor girl dressed in mourning, who travels on foot. She arrived about an hour ago; she is resting now, but she wants to set off again at sunset, despite what anyone may have told her. By Saint Thomas, my patron! she seems to fear neither God, nor devil, nor fanatic, nor prophet... What a girl! Jesus-God! a steel corslet would suit her better than a bodice! And where is she going? To Saint-Andéol-de-Clerguemot; it’s two leagues from Pont-de-Montvert.

You see, madam, that if she wants to take you where you need to go, it won’t trouble her much. And where is this young girl? Can I see her? Send her to me, said Toinon quickly; I will pay her whatever she wants, if she agrees to serve as my guide. Thomas Rayne shook his head. This poor young girl seems prouder than the wife of a count, madam. Seeing that she was traveling on foot and believing her to be poor, when she wanted to pay me for the piece of bread, the glass of water, and the grilled eggplants she modestly ate, I told her: Keep your money, my good girl, Thomas Rayne did not take the sign of the Pastoral Cross for nothing. Say a prayer for me, and I will be well repaid for my alms.

But, God in heaven! At that mention of prayer and alms, the young girl shot me a look so furious, with her money-related piety, that in the future I would rather ask my hosts for double the fare than give them merely the generosity of a glass of water! She is proud; that's good; she might understand me. She is in the small room next to the press, said Thomas Rayne. The path is dark; if madam wants to follow me, I will guide her.

But, God in heaven! At that mention of prayer and alms, the young girl shot me a look so furious, with her money-related piety, that in the future I would rather ask my hosts for double the fare than give them merely the generosity of a glass of water! She is proud; that's good; she might understand me. She is in the small room next to the press, said Thomas Rayne. The path is dark; if madam wants to follow me, I will guide her.

Toinon followed the innkeeper. After crossing a courtyard, she arrived in a fairly long corridor. Not caring, perhaps, about being with the young girl he had inadvertently offended, Thomas stopped and quietly said to the Psyche, pointing to an ajar door: Here is her room, madam. And he disappeared. Toinon, too preoccupied with her resolution to feel intimidated, gently pushed the door and entered.

Doubtless exhausted from the journey, the young girl was sleeping. She was so beautiful, despite the poverty of her clothing; her beauty had such an energetic and grand character that Toinon stood for a moment, stunned in admiration. This small, dark room was lit by a bull's-eye window, placed quite high, which filtered a vivid and rare light onto the straw bed where the young girl rested, dressed in a long black coarse cloth dress; a hooded cloak of the same fabric, called “gaulle” in Lower Languedoc, lay on a chair beside her, along with her iron-tipped staff, a leather knapsack, and her dusty sandals.

Doubtless exhausted from the journey, the young girl was sleeping. She was so beautiful, despite the poverty of her clothing; her beauty had such an energetic and grand character that Toinon stood for a moment, stunned in admiration. This small, dark room was lit by a bull's-eye window, placed quite high, which filtered a vivid and rare light onto the straw bed where the young girl rested, dressed in a long black coarse cloth dress; a hooded cloak of the same fabric, called “gaulle” in Lower Languedoc, lay on a chair beside her, along with her iron-tipped staff, a leather knapsack, and her dusty sandals.

The noble profile of the young girl stood out in the light against the shadows of the alcove: she seemed to be a model for one of the ardent and dark figures of Murillo or Zurbarán. She had a broad forehead, a straight and somewhat long nose, full, uplifted lips, a prominent chin, and an eyebrow almost as straight as the ebony brow that framed it. Her hair, a blue-black with lustrous highlights, slightly frizzed by the moisture of the water in which the young girl had likely bathed her face, fell in natural curls around a neck of antique purity. The fresh down of youth softened her sun-kissed complexion. Although she was pale, the lively brown of her skin indicated strength and health.

She was tall, and her broad shoulders, as well as her strong hips, further emphasized her slender and graceful figure. The sleeves of her dress, raised during her sleep, revealed her bare, round, and muscular arms: one hung almost to the ground, while the other supported her head. Her hands and beautiful feet, although slightly tanned, showed by the elegance of their shapes that she did not usually engage in long fatigue or hard labor.

She was tall, and her broad shoulders, as well as her strong hips, further emphasized her slender and graceful figure. The sleeves of her dress, raised during her sleep, revealed her bare, round, and muscular arms: one hung almost to the ground, while the other supported her head. Her hands and beautiful feet, although slightly tanned, showed by the elegance of their shapes that she did not usually engage in long fatigue or hard labor.

Toinon examined this wild beauty in silence, with a curiosity mixed with fear; suddenly the young girl moved, and her face, instead of remaining in profile, turned to face her. In this new aspect, the expression of her face seemed to Toinon dark, violent, almost threatening. The young girl was dreaming, a bitter and painful smile flickering across her lips. She furrowed her black brows, shaking her head on the pillow two or three times; then, still lost in thought, she murmured in a low and broken voice, these disjointed words: Jean... no, I am not guilty... Cavalier, I swear it... my father... dead... the Marquis de Florac... infamous... oh! infamous... infamous! She pronounced these last words with such increasing energy, with so much exaltation, that when she said the word “infamous” for the third time, she jolted awake. Toinon had never seen this young girl, but upon hearing those words about the infamous Marquis de Florac, Psyche was convinced by a hidden revelation—a true marvel of love—that there was some fatal secret between this woman and Tancrède.

Toinon had listened to Larose's account with rapt attention and a consuming anxiety; the slightest details of this narrative had etched themselves in her mind, and the name of Cavalier, one of the rebel leaders, especially lingered in her memory as that of one of Mr. de Florac’s most dangerous enemies. Now, this young girl had also uttered those words in her sleep: Cavalier, I swear it... What mysterious connection could exist between these three characters: the young girl, Cavalier, and Tancrède?

Psyche did not yet grasp this secret. But at the painful blow that had just echoed in her heart, at the fervor of her hatred, jealousy, and piercing curiosity, at her instinctive terror, she felt at that moment that Isabeau (for that was her name) must be the most deadly enemy of Tancrède. In light of these fears, Toinon had to do everything possible to persuade Isabeau to serve as her guide, hoping to spy on her during the journey and to divert from Tancrède the misfortunes she feared for him.

Psyche did not yet grasp this secret. But at the painful blow that had just echoed in her heart, at the fervor of her hatred, jealousy, and piercing curiosity, at her instinctive terror, she felt at that moment that Isabeau (for that was her name) must be the most deadly enemy of Tancrède. In light of these fears, Toinon had to do everything possible to persuade Isabeau to serve as her guide, hoping to spy on her during the journey and to divert from Tancrède the misfortunes she feared for him.

Isabeau, seeing a stranger near her bed upon waking, stood up abruptly. She appeared even taller to Toinon when standing than when lying down. What do you want? Isabeau said harshly, frowning her ebony brows and fixing on the Psyche a dark, profound gaze like the night. To talk to you, Toinon replied resolutely, her large, bright gray eyes not lowering before Isabeau's dark glance. These two women, so different by nature, examined each other in silence: one proud, tall, and strong, the other small, supple, and nervous. It was as if a lioness was ready to roar at a serpent. After this first moment, involuntarily given to the expression of a suppressed, deep-seated hatred, Toinon reflected that it was a matter of cunning and not violence with this woman, and that it was not by defying her that she would convince her to serve as a guide.

The Psyche therefore called upon all her resources, all the hypocrisies of her art; a practiced actress, she timidly lowered her beautiful eyes, which quickly extinguished their spark of passing anger in a tear of angelic sadness; her childlike mouth shaped the most touching, most naïve smile, her two small hands rose in supplication, she bent her knees halfway and said in a soft, trembling voice: Forgive me, miss, but alas! I come to ask you for a great service. I am alone, I am poor, I cannot help anyone, Isabeau replied curtly.

The Psyche therefore called upon all her resources, all the hypocrisies of her art; a practiced actress, she timidly lowered her beautiful eyes, which quickly extinguished their spark of passing anger in a tear of angelic sadness; her childlike mouth shaped the most touching, most naïve smile, her two small hands rose in supplication, she bent her knees halfway and said in a soft, trembling voice: Forgive me, miss, but alas! I come to ask you for a great service. I am alone, I am poor, I cannot help anyone, Isabeau replied curtly.

If you would deign to consent, you could do everything for me, miss, said the Psyche, falling to her knees. I am Protestant, said Isabeau, stepping back a pace, believing this declaration would cut the conversation short. And so am I! said Toinon in a low voice, making a mysterious sign. The Psyche had risked this lie, without foreseeing the consequences, but she was only thinking of the present moment, and her mind, exalted by the difficulty of her situation, suggested to her at that moment a rather plausible fable. You are of the Reformed religion? Isabeau resumed in a less harsh voice, fixing a penetrating gaze on Toinon. Alas yes, my mother and my sisters are prisoners at Pont-de-Montvert.

I have just arrived from Paris to join them, but the postilion who brought me refuses to travel, fearing the rebels, as they say. No one wants to serve as my guide. The innkeeper told me you were going toward Pont-de-Montvert. Out of pity, let me accompany you. If you have a mother, sisters, a father, miss, you will understand all that I suffer, all that I desire! And the Psyche, weeping, embraced Isabeau's knees. Get up, get up, said Isabeau with a tender air; then she added: I have no sister, I have no mother, I have no father; but you are of our religion, and I must do for you all that I would do for my sister. Then, after a moment of silence, she said to Toinon: One can tell by your accent that you are not from this country... La Revue de Paris 1928

Former holiday hotel with a garden along the Allier, L'Etoile Guest House is located in La Bastide-Puylaurent between Lozere, Ardeche, and the Cevennes in the mountains of Southern France. At the crossroads of GR®7, GR®70 Stevenson Path, GR®72, GR®700 Regordane Way, GR®470 Allier River springs and gorges, GRP® Cevenol, Ardechoise Mountains, Margeride. Numerous loop trails for hiking and one-day biking excursions. Ideal for a relaxing and hiking getaway.

Copyright©etoile.fr